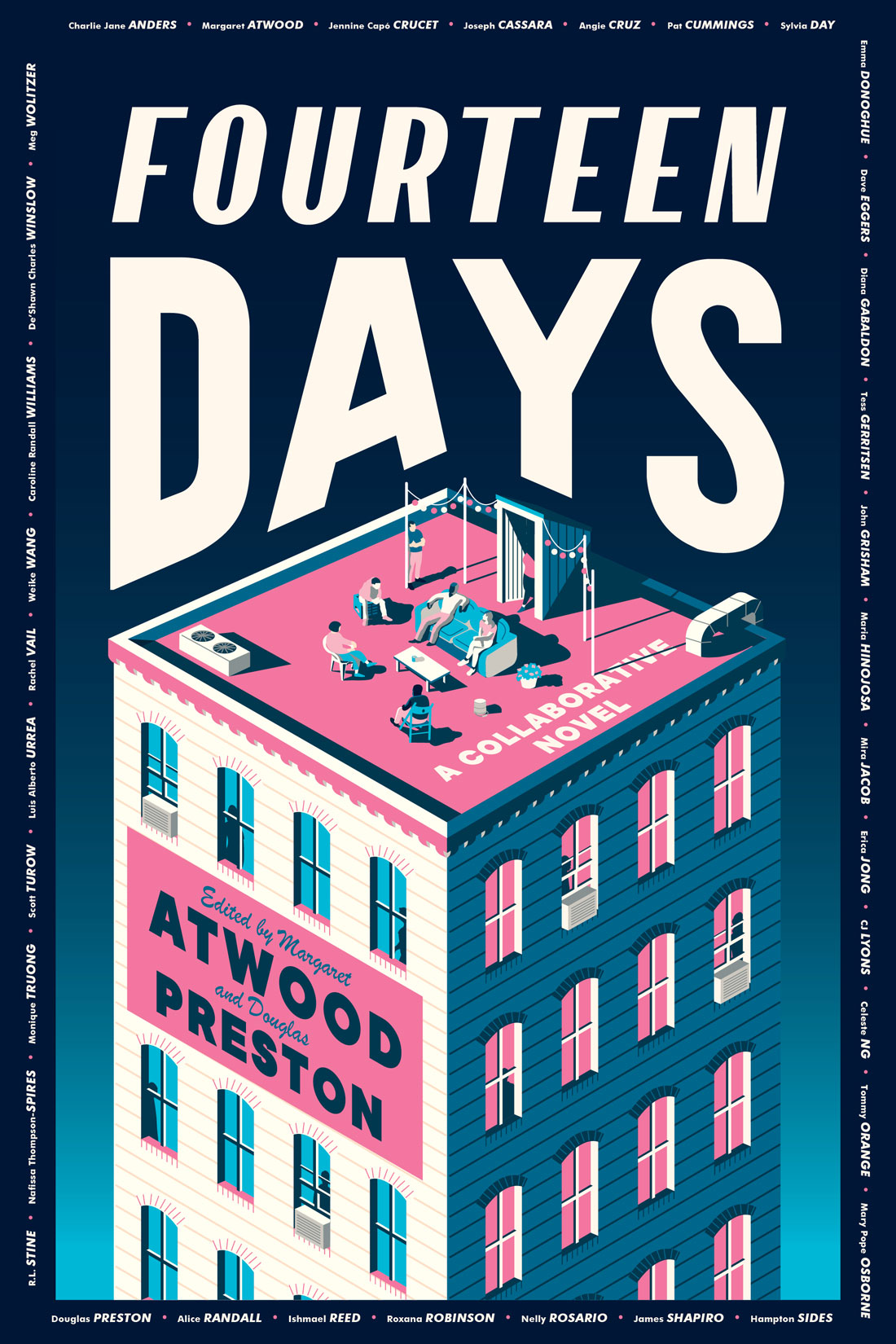

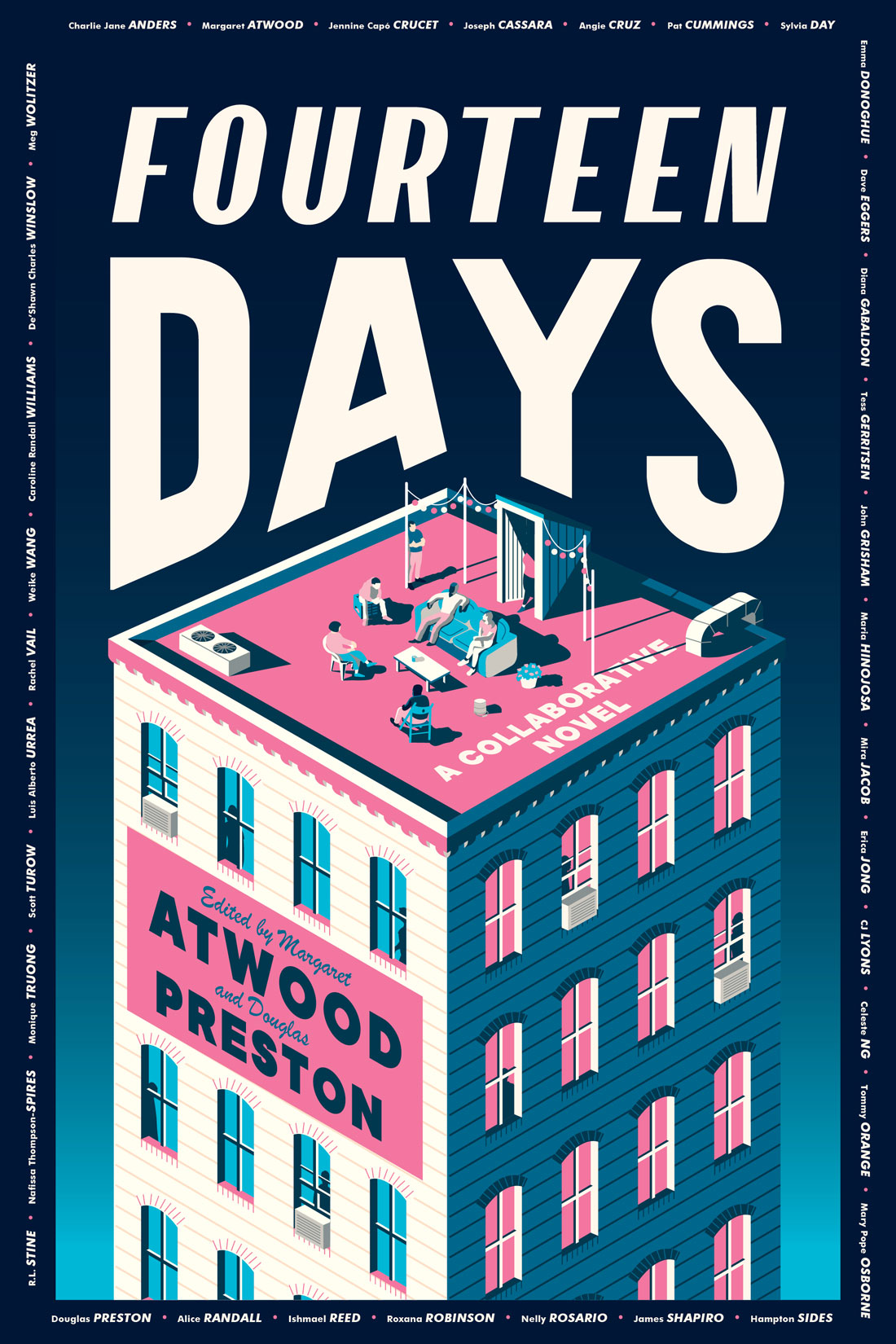

Fourteen Days: A Collaborative Novel

Audio:

Or, read this teaser description first, (it's from the book's back cover / jacket flap) and get a taste:

Set in a Lower East Side tenement in the early days of the COVID-19 lockdowns, Fourteen Days is a surprising and irresistibly propulsive novel with an unusual twist: each character in this diverse, eccentric cast of New York neighbors has been secretly written by a different, major literary voice.

One week into the COVID-19 shutdown, tenants of a Lower East Side apartment building in Manhattan have begun to gather on the rooftop and tell stories. With each passing night, more and more neighbors gather, bringing chairs and milk crates and overturned pails. Gradually the tenants—some of whom have barely spoken to each other—become real neighbors. In this Decameron-like serial novel, general editor Margaret Atwood, Authors Guild president Douglas Preston, and a star-studded list of contributors create a beautiful ode to the people who couldn’t get away from the city when the pandemic hit. A dazzling, heartwarming collection, Fourteen Days reveals how beneath the horrible loss and suffering, some communities managed to become stronger.

Includes writing from:

Charlie Jane Anders, Margaret Atwood, Jennine Capó Crucet, Joseph Cassara, Angie Cruz, Pat Cummings, Sylvia Day, Emma Donoghue, Dave Eggers, Diana Gabaldon, Tess Gerritsen, John Grisham, Maria Hinojosa, Mira Jacob, Erica Jong, CJ Lyons, Celeste Ng, Tommy Orange, Mary Pope Osborne, Douglas Preston, Alice Randall, Caroline Randall Williams, Ishmael Reed, Roxana Robinson, Nelly Rosario, James Shapiro, Hampton Sides, R.L. Stine, Nafissa Thompson-Spires, Monique Truong, Scott Turow, Luis Alberto Urrea, Rachel Vail, Weike Wang, De’Shawn Charles Winslow, and Meg Wolitzer!

please make sure you have ad blockers turned off.

Ordering Options

Ordering Options

Excerpt

Excerpt

Genre: Contemporary Fiction

Publication Date:

February 6, 2024

Ordering Options

Ordering Options

Audio Excerpt

Audio Excerpt

Day 1

March 31, 2020

Call me 1A. I’m the super of a building on Rivington Street on the Lower East Side of New York City. It’s a six-floor walk-up with the farcical name of the Fernsby Arms, a decaying crapshack tenement that should have been torn down long ago. It’s certainly not keeping up with the glorious yuppification of the neighborhood. As far as I know, nobody famous has ever lived here; there have been no serial killers, subversive graffiti artists, notorious drunken poets, radical feminists, or Broadway song pluggers commuting to Tin Pan Alley. There might have been a murder or two–the building looks it–but nothing that made the New York Times. I hardly know the tenants at all. I’m new here–got the job a few weeks ago, around the time the city was shut down by Covid. The apartment came with the job. Its number, 1A, sounded like it was on the first floor. But when I got here–and it was too late to back out–I found it was actually in the basement and as dark as the broom closet of Hades and a cell phone dead zone to match. The basement in this building is the first floor, the second floor is the real first floor, and so on up to six. A con.

The pay in the Fernsby Arms is rotten, but I was desperate, and it kept me from winding up on the street. My father came here from Romania as a teenager, married, and worked like a dog as the super of a building in Queens. And then I was born. When I was eight, my mom left. I tagged along as Dad fixed leaky faucets, changed lightbulbs, and dispensed wisdom. I was pretty adorable as a kid, and he brought me along to increase his tips. (I’m still adorable, thank you very much.) He was one of those supers people liked to confide in. While he was plunging a shit-blocked toilet or setting out roach motels, the ten- ants liked to pour out their troubles. He’d sympathize, offering benediction and reassurance. He always had an old Romanian saying to comfort them, or some tidbit of ancient wisdom from the Carpathian Mountains–that plus his Romanian accent made him sound wiser than he really was. They loved him. At least some of them did. I loved him, too, because none of this was for show, it’s how he really was, a warm, wise, loving, faux-stern kind of dad–his one drawback being that he was too Old World to realize how much his ass was being mowed every day by Life in America. Suffice to say, I did not inherit his kindly, forgiving nature.

Dad wanted a different life for me, far away from having to fix other people’s shit. He saved like mad so I could go to college; I got a basketball scholarship to SUNY and planned to be a sportscaster. We argued about that–Dad wanted me to be an engineer ever since I won the First Lego League robotics prize in fifth grade. College didn’t work out. I got kicked off the college basketball team when I tested positive for weed. And then I dropped out, leaving my dad $30,000 in debt. It wasn’t $30,000 in the beginning; it started out as a small loan to supplement my scholarship, but the vig grew like a tumor. After leaving school,I moved to Vermont for a bit and lived off a lover’s generosity, but a bad thing happened, and I moved back in with my dad, waiting tables at Red Lobster in Queens Place Mall. When Dad started going downhill from Alzheimer’s, I covered up for him as best I could in the building, fixing stuff in the mornings before going to work. But eventually, a miserable toad in the building reported us to the landlord, and he was forced to retire. (Using my master key, I flushed a bag of my Legos down her toilet as a thank-you.) I had to move him to a home. We had no money, so the state put him in a memory care center in New Rochelle. Evergreen Manor. What a name. Evergreen.The only thing green about it are the walls–vomit-puss-asylum green, you know the color. Come for the lifestyle. Stay for a lifetime. The day I moved him in, he threw a plate of fettuccini Alfredo at me. Up until the lockdown, I’d been visiting him when I could, which hasn’t been much because of my asthma and the ongoing shitsaster known as My Life.

All these bills started pouring in related to Dad’s care and treatment, even though I thought Medicare was supposed to pay. But no, they don’t. Just you wait until you’re old and sick. You should have seen the two-inch stack I burned in a wastebasket, setting off the fire alarms. That was in January. The building hired a new super–they didn’t want me because I’m a woman, even though I know that building better than anyone–and I was given thirty days to move out. I got fired from Red Lobster because I missed too many days taking care of my dad. The stress of no job and looming homelessness brought on another asthma attack, and they raced me to the ER at Presbyterian and stuck me full of tubes. When I got out of the hospital, all my shit had been taken from the apartment–everything, Dad’s stuff, too. I still had my phone, and there was an offer in my email for this Fernsby job, with an allegedly furnished apartment, so I jumped on it.

Everything happened so quickly. One day the coronavirus was something going on in Wu-the-hell-knows-where-han, and the next thing you know, we’re in a global pandemic right here in the US of A. I had been planning to visit Dad as soon as I’d moved into a new place, but in the meantime I’d been FaceTiming him at Pukegreen Manor almost every day with the help of a nurse’s aide. Then all of a sudden, they called out the National Guard to surround New Rochelle, and Dad was at ground zero, blocked off from the rest of the world. Worse, I suddenly couldn’t get anyone on the phone up there, not the reception desk or the nurse’s cell or Dad’s own phone. I called and called. First it just rang, endlessly, or someone took the phone off the hook and it was busy forever, or I got a computer voice asking me to leave a message. In March, the city got shut down because of Covid, and I found myself in the aforesaid basement apartment full of weird junk in a ramshackle building with a bunch of random tenants I didn’t know.

I was a little nervous because most people don’t expect the super to be a woman, but I’m six feet tall, strong as heck, and capable of anything. My dad always said I was “strălucitor,” which means radiant in Romanian, which would be such a dad thing to say, except it happens to be true. I get a lot of attention from men–unwanted, obviously, since I don’t swing that way–but they don’t worry me. Let’s just say I’ve handled my share of fuckwad men in the past, and they’re not going to forget it any time soon, so trust me, I can handle whatever this super job throws at me. I mean, Dracula was my great-grandfather thirteen times removed, or so Dad claims. Not Dracula the dumbass Hollywood vampire, but Vlad Dracula III, king of Walachia, also known as Vlad the Impaler–of Saxons and Ottomans. I can figure out and fix anything. I can divide in my head a five-digit number by a two-digit number, and I once memorized the first forty digits of pi and can still recite them. (What can I say: I like numbers.) I don’t expect to be in the Fernsby Arms forever, but for the moment, I can tough it out. It’s not like Dad’s in a position to be disappointed in me anymore.

When I started this job, the retiring super was already gone. Guess not every building wipes out all the super’s stuff when they leave, ’cause the apartment was packed with his junk and, man, the guy was a hoarder. I could hardly move around, so the first thing I did, I went through it all and made two piles–one for eBay and the other for trash. Most of it was crap, but some if it was worth good money, and there were a few items I had hopes might be valuable. Did I mention I need money?

To give you an idea of what I found, here’s a random list: six Elvis 45s tied in a dirty ribbon, glass prayer hands, a jar of old subway tokens, a velvet painting of Vesuvius, a plague mask with a big curved beak, an accordion file stuffed with papers, a blue butterfly pinned in a box, a lorgnette with fake diamonds, a wad of old Greek paper money. Most wonderful of all was a pewter urn full of ashes and engraved Wilbur P. Worthington III, RIP. Wilbur was a dog, I assume, though he could have been a pet python or wombat, for all I know. No matter how hard I looked, I couldn’t find anything personal about the old super, even his name. So I’ve come to think of him as Wilbur, too. I picture him as an old man with a harrumphing, what-do-we-have- here manner, unshaven, evaluating a broken windowshade with his wet lips sticking out pensively, making little grunts. Wilbur P. Worthington III, Superintendent,The Fernsby Arms.

Eventually, in the closet I found a hoard of something far more to my liking: a rainbow array of half-empty liquor bottles, spirits, and mixers crowding every shelf from top to bottom.

The accordion file intrigued me. Inside were a bunch of miscellaneous papers. They were not the super’s scribblings, for sure–these were documents he’d collected from somewhere. Some were old, typed with a manual typewriter, some printed by computer, and a few handwritten. Most of them seemed to be first-person narratives, incomprehensible, rambling stories with no beginning or end, no plot, and no bylines–random splinters and scraps of lives. Many were missing pages, the narratives beginning and ending in the middle of sentences. There were also some long letters in there, too, and unintelligible legal documents. All this stuff was mine, I supposed, and I was sick when I thought of how this alien trash was all I had in the world, replacing everything I used to own that my dad’s building had thrown out.

But among the stuff in the apartment was a fat binder, sitting all by itself on a wooden desk with peeling veneer, a chewed Bic pen resting on top of it. When I say “chewed,” I mean half-eaten, my mysterious predecessor having gnawed off at least an inch from the top. The desk-top was about the only neatly organized place in the apartment.The handmade book immediately intrigued me. Its title was on the cover, drawn in Gothic script: The Fernsby Bible. On the first page, the old super had clipped a note to the new super–that is, me–explaining that he was an amateur psychologist and trenchant observer of human nature, and that these were his research notes, collected on the residents. They were extensive. I paged through it, amazed at the thoroughness and density of the work. And then at the end of the binder, he had added a mass of blank pages, with the heading “Notes and Observations.” And then he’d added a small note at the bottom: “(For the Next Superintendent to Fill In.)”

I looked at those blank pages and thought to myself that the old super was crazy to think his successor–or anyone, for that matter–would want to fill them up. Little did I know the magical allure that a half-eaten pen and blank paper would have on me.

I turned back to the super’s writings. He was prolific, filling pages and pages of accounts of the tenants in the building, penned in a fanatically neat hand–with sharp comments on their histories, quirks and foibles, what to watch out for, and all-important descriptions of their tipping habits. It was packed with stories and anecdotes, asides and riddles, factoids, flatulences, and quips. He had given everyone a nickname. They were funny and cryptic at the same time. “She is the Lady with the Rings,” he wrote of the tenant in 2D. “She will have rings and things and fine array.” Or the tenant in 6C: “She is La Cocinera, sous-chef to fallen angels.” 5C: “He is Eurovision, a man who refuses to be what he isn’t.” Or 3A: “He is Wurly, whose tears become notes.” A lot of his nicknames and notes were like these–riddles. Wilbur must’ve been a champion procrastinaut, writing in this book instead of fixing leaky faucets and broken windows in this shithole of a building.

As I read through those bound pages I was transfixed. Aside from the strangeness of it all, they were pure gold to this newbie super. I set out to memorize every tenant, nickname, and apartment number. It’s my essential reading. Ridiculous as it is, I’d be lost without The Fernsby Bible. The building’s a shambles, and he apologized about that, explaining that the absentee landlord didn’t respond to requests, won’t pay for anything, won’t even answer the damn phone–the bastard is totally AWOL. “You’ll be frustrated and miserable,” he wrote, “until you realize:You’re on your own.”

On the back cover of the bible, he scotch-taped a key with a note. “Check it out.”

I thought it was a master key to the apartments, but I tested it and found out it wasn’t. It was a strangely shaped key that didn’t even fit into the many locks I tried it on. I became intrigued and, as soon as I could, I started going through the building methodically, testing it in every lock, to no avail. I was about to give up when, at the end of the sixth-floor hall, I found a narrow staircase to the roof. At the top was a padlocked door–and lo and behold, the key slipped right into that padlock! I opened the door, stepped out, and looked around.

I was stunned. The rooftop was damn near paradise, never mind the spiders and pigeon shit, and loose flapping tarpaper. It was big, and the panorama was stupendous. The tenements on either side of the Fernsby Arms had recently been torn down by developers, and the building stood alone in a field of rubble–with drop-dead views up and down the Bowery and all the way to the Brooklyn Bridge, the Williamsburg Bridge, and the downtown and midtown skyscrapers. It was evening, and the whole city was tinged with pinkish light, a lone jet contrail crossing overhead in a streak of brilliant orange. I yanked my phone out of my pocket–five bars. As I looked around, I thought, What the hell? I could finally call Dad from up here, hopefully reach him at last, if it was just a reception problem keeping me from getting through at Upchuck Manor. It was certainly illegal to be up on the roof, but the landlord sure wasn’t going to be coming into the Covid-ridden city to check on his properties. With the lockdown now stretching almost two weeks, this rooftop was the only place a body could get fresh air and sun that felt halfway safe anymore. One day the developers would put up hipster glass towers, burying the Fernsby Arms in permanent shadow. Till then, though, why shouldn’t it be mine? Obviously, good old Wilbur P. Worthington III had felt the same way, and he wasn’t even here for lockdown.

As I scoped the place out, I immediately noted a big lumpy thing sitting out in the open, covered with a plastic tarp. I yanked it off, revealing an old mouse-chewed fainting couch in soiled red velvet–the old super’s hangout, for sure. As I eased down on it to test its comfort, I thought, God bless Wilbur P. Worthington the Third!

I began to come to the roof every evening, at sunset, with a thermos of margaritas or some other exotic cocktail I’d scrounged up from my rainbow room of liquor, and I stretched out on my couch and watched the sun set over Lower Manhattan while I dialed Dad’s number over and over again. I still couldn’t reach him, but at least I got a good buzz on while trying.

My solitary paradise, such as it was, didn’t last long. A couple of days ago, in this last week in March, as Covid was setting the city on fire, one of the tenants cut the lock off the door and put a plastic patio chair up there, with a tea table and a potted geranium. I was seriously cheezed. Good old Wilbur had kept a collection of locks along with his other junk, so I picked up a monstrous, case-hardened, chrome-and-steel padlock, heavy enough to split the skull of a moose, and clapped it on the door. It was guaranteed not to be cut or three times your money back. But I guess they wanted their freedom as much as I did, because someone took a crowbar to the lock and hasp and wrenched them off, cracking the door in the process. There was no locking it after that. Try buying a new door during Covid.

I’m pretty sure I know who did it. When I stepped out onto the roof after finding the busted door, there was the culprit, curled up in a “cave chair”–one of those seat things shaped like an egg covered in faux-fur that you crawl into–vaping and reading a book. It must have been hell schlepping that chair all the way up to the roof. I recognized her as the young tenant in 5B, the one Wilbur called Hello Kitty in his bible because she wore sweaters and hoodies with that cartoon character on it. She gave me a cool look, as if challenging me to accuse her of busting the door. I didn’t say anything. What was I gonna say? Besides, I had to respect her a little for that. She reminded me of myself. And it’s not like we had to talk to each other–she seemed as keen to ignore me as I was in ignoring her. So I kept my distance.

After that, though, other tenants began discovering the rooftop, a few at a time. They dragged their ugliest chairs up the narrow stairs and parked themselves at sunset, everyone staying “socially distanced,” the new phrase du jour. I did try to stop them. I posted a sign saying that it was illegal (technically true!), that nobody was supposed to be up there, that someone could trip and fall off the low parapets. But at this point, we’d been under lockdown for what already felt like a lifetime, and people would not be barred from fresh air and a view. I can’t blame them. The building is dark, cold, and drafty; the hallways have weird smells; and there are cracked and broken windows everywhere. Besides, the rooftop feels big enough still–everyone is careful not to touch, talk loudly, or even blow their noses, and we’re all keeping six feet apart. Too bad you can’t find any hand sanitizer in this damn city, or I’d park a jeroboam of it at the door. As it is, I bleach the doorknobs once a day. And I’m not worried for myself–I’m only thirty, young enough that they say the virus won’t come for me, except for my asthma.

Still, I missed my private domain.

Meanwhile, Covid was hitting the city hard. On March 9, the mayor announced that there were sixteen cases in the city; by March 13, as I mentioned, the National Guard was surrounding New Rochelle; and on March 20, New York was shut down, just in time for everyone to binge-watch Tiger King. A week later, infections surpassed twenty-seven thousand, with hundreds dying every day and cases soaring. I pored over the statistics and then, fatefully, I guess, began recording them in the blank pages in the back of Wilbur’s book, his so-called Fernsby Bible.

Naturally, anyone who could had already left New York. The wealthy and professional classes fled the city like rats from a sinking ship, skittering and squeaking out to the Hamptons, Connecticut, the Berkshires, Cape Cod, Maine–anywhere but New Covid City. We were the left-behinds. As the super, it’s my job–or so I assume–to make sure Covid doesn’t get in here and kill the tenants at the Fernsby Arms. (Except the rent-controlled ones–ha ha, no need to bleach their doorknobs, I’m sure the landlord would have told me.) I circulated a notice laying out the rules: no outside people allowed in the building, everybody six feet apart in common areas, no congregating in stairways. And so on and so forth. Just like Dad would have done. No guidance yet from the powers that be about masks, since there aren’t enough for the healthcare workers, anyway. We are pretty much stuck in the building for the duration–locked down.

So every evening, the tenants who had discovered the roof came up and hung out. There were six of us at first. I looked them all up in The Fernsby Bible. There was Vinegar from 2B, Eurovision from 5C, the Lady with the Rings from 2D, the Therapist from 6D, Florida from 3C, and Hello Kitty from 5B. A couple of days ago, New Yorkers started doing this thing of cheering the doctors and other frontline workers at seven o’clock, around sunset. It felt good to do something, and to break up the routine. So people got in the habit of gathering on the roof right before seven, and when the time rolled around, we all clapped and cheered from our rooftop along with the rest of the city, and we banged on pots and whistled. That was the start of the evening. I brought up a cracked lantern I found in Wilbur’s junk, which held a candle. Others carried up lanterns and candle holders with hurricane shields–enough to create a small lighted area. Eurovision had an antique brass kerosene lantern with a decorated glass shade.

In the beginning, no one talked, and that was just fine with me. Having seen the way my dad got treated by the folks he’d lived with and helped for years, I didn’t want to get to know them. I wouldn’t even be here with them except it had been my space first. A super who thinks she can make friends in her building is asking for trouble. Even in a merde shed like this, everyone considers themselves above the super. So my motto is, Keep your distance. And they clearly didn’t want to know me, either. Good.

Since I was new, everyone up there was a stranger. They spent their time flicking at their phones, pounding down beers or glasses of wine, reading books, smoking weed, or messing with a laptop. Hello Kitty sat herself downwind in that chair and vaped almost nonstop. I once caught a whiff of her vape smoke, and it was some sickly sweet watermelon smell. She sucked on that thing literally nonstop, like breathing. A wonder she wasn’t dead. With the stories coming out of Italy of folks on ventilators, even if it’s mostly old people, I wanted to smack that shit out of her hand. But we’re all entitled to our vices, I guess, and besides, who’s going to listen to the super? Eurovision brought up one of those miniature Bose Bluetooth speakers, where it sat next to his chair playing soft Europop. Nobody in our building ever seemed to go out, as far as I could tell, even for groceries or toilet paper. We were in full lockdown mode.

Meanwhile, because we were so close to Presbyterian Downtown Hospital, the ambulances howled up and down the Bowery, their sirens getting louder as they approached and then sinking into a dying wail as they went by. All these unmarked refrigerated trucks started showing up. We soon learned they were carrying the dead bodies of Covid victims, and they rumbled through the streets like the plague carts of old, day and night, stopping all too frequently to pick up shrouded cargo.

Tuesday, March 31–today–was a sort of milestone for me, because it was the day I started writing things down in this book. I was originally planning to just record numbers and statistics, but it kind of got away from me and grew into a bigger project. Today’s numbers were a kind of milestone: the New York Times reported that the city had surpassed a thousand Covid deaths. There were 43,139 cases in the city, and 75,795 in the state. In the five boroughs, Queens and Brooklyn were being trashed the most by Covid, with 13,869 and 11,160 cases respectively; the Bronx had 7,814, Manhattan 6,539, and Staten Island 2,354. Recording the numbers seemed to domesticate them, make them less scary.

It rained in the afternoon. I got up on the rooftop as usual, about fifteen minutes before sunset. The evening light cast long shadows down the rain-slicked Bowery. In between the sirens, the city was empty and silent. It was strange and oddly peaceful. There were no cars, no horns, no pedestrians surging home along the sidewalks, no drone of planes overhead. The air was washed and clean, full of dark beauty and magical portent. Without the fumes from cars, it smelled fresh, reminding me of my short happy life in Vermont, before… well, anyway. The usual tenants gathered on the rooftop as the streets slipped into dusk. When seven o’clock came around, and we heard the first whoops and bangs from the surrounding buildings, we heaved ourselves out of our chairs and did the usual whistling, clapping, cheering thing–all except the tenant in 2B. She just sat there trying to get her phone to work. Wilbur had warned me about her: she was the regal type who called to get a lightbulb changed, but at least she tipped like royalty. “She is pure native New York vinegar,” he wrote, and added one of his riddles: “The best wine doth make the sharpest vinegar.” Whatever that means. I figured she was in her fifties–dressed in all black, with a black T-shirt and faded black skinny jeans. The dribbles and splatters of paint on her well-worn Doc Martens were the only color on her. She was, I figured, an artist.

The woman in 3C, given the name of Florida in the book, called out Vinegar. “Aren’t you going to join us?” I immediately sensed from her tone that there was history between them. Florida–the old super had not explained the origin of the name, maybe that was just how she was known–was a large, big-breasted woman who managed to convey a restless energy, age about fifty, with perfect salon hair and a sequined shirt covered with a shimmering golden shawl. The bible described her as a gossip, with the quip: “Gossip is chatter about the human race by lovers of the same.”

Vinegar returned Florida’s look with a frosty one of her own. “No.”

“What you mean, no?”

“I’m tired of shouting ineffectually at the universe, thank you.”

“We’re cheering the frontline workers–the people out there risking their lives.”

“Well, aren’t you the high and holy one,” said Vinegar. “How’s yelling going to help them?”

Florida stared at Vinegar.“There’s no logic to it. Esto es una mierda, and we’re trying to show support.”

“So you thinking banging on a pot is going to make a difference?”

Florida pulled the golden shawl closer around her shoulders, compressed her lips in judgment, and eased herself back in the chair.

“When this is all over,” said the Lady with the Rings after a moment, “it’ll be like 9/11. Nobody will talk about it. It will be like someone who committed suicide–you never talk about them.”

“People don’t talk about 9/11,” said the Therapist, “because New York got a dose of PTSD from it. I still have 9/11 patients working through PTSD. Twenty years later.”

“What do you mean, people don’t talk about 9/11?” Hello Kitty said.“They won’t stop talking about it. You’d think half of New York City was down there running for their lives, choking on the smoke and dust. It’ll be the same with this. Let me tell you all about how I survived the Great Pandemic of Two Thousand and Twenty. People won’t shut up about it.”

“My, my,” said Vinegar. “Were you even alive when 9/11 happened?”

Hello Kitty sucked on her vape and ignored her.

“Think about all the PTSD this pandemic’s going to trigger,” said Eurovision. “Oh God, we’re going to be in analysis forever.” He gave a little laugh and turned to the Therapist.“What a windfall for you!”

She responded with a stony look.

“Everyone has PTSD these days,” Eurovision went on, “I’ve got PTSD from the cancellation of Eurovision 2020. It’s the first one I’ve missed since 2005.” He clutched his chest and made a face.

“What’s Eurovision?” Florida asked.

“The Eurovision Song Contest, darling. Singers from all over the world are chosen to compete with an original song, one singer or group per country. A winner is voted on. Six hundred million watch it on TV. It’s the World Cup of music. It was supposed to be in Rotterdam this year, but last week they canceled it. I had my plane tickets, hotel, everything. So now”–he fanned himself in an exaggerated manner–“Help me, Doc, I have PTSD.”

“PTSD is not a joking matter,” said the Therapist.“And neither was 9/11.”

“Nine/eleven is still with us,” a woman in her thirties added. I recognized her from the book as Merenguero’s Daughter, 3B. “It’s fresh. It touched all of us, including my family. Even back in Santo Domingo.”

“You lost someone in 9/11?” the Lady with the Rings asked, a challenge in her tone.

“In a weird way, yes.”

“How so?”

She took a deep breath. “Mi papá was this big merenguero, which, if you don’t know, means he played merengue for a living. He used to spend a lot of his time at El Show del Mediodía or The Midday Show. If there’s one show in the Dominican Republic that everyone watches, it’s that show. In fact, it’s still on TV today.”

As she started talking, I knew she was about to launch into a story, and I had an idea. Since my early twenties, I’ve been in the habit of recording the stuff people are saying around me, especially the shit from guys who come on to me in a bar. I’d just casually leave my phone on the bar or table or in my pocket; or at other times on the subway, I’d pretend to be messing with my phone all the while recording what some jackass was saying. You wouldn’t believe what I’ve collected over the years, many glorious hours of idiocy and obnoxiousness recorded for posterity. Makes me wish I could monetize it on YouTube or something. And it’s not just the bad, actually. I’ve captured other things, too–tales of woe, funny stories, kindnesses, confessions, dreams, nightmares, reminiscences, even crimes. The things strangers will tell you late at night on the E train… I once was so desperate, I smoked dog shit to get high… I spied on my grandparents having sex, and you wouldn’t believe what they were doing… I won a hundred-dollar bet by skinning, cooking, and eating my brother’s gerbil.

My dad collected people by charm. I collected them by stealth.

Anyway, so I started recording. My couch was situated too far away from Merenguero’s Daughter, though, so I got up and, with a show of eagerness to listen, I dragged the damn red sofa through the six-foot spaces between everyone’s chairs, giving them all a big dumb grin and muttering something about not want to miss a single word. I made myself comfortable and slipped my phone out of my pocket, pretended to check something on it, oriented it, and hit Record. Then I casually placed it on the couch, pointing at Merenguero’s Daughter, and settled back with my feet up, margarita in hand.

What will I do with the recording? I didn’t know right in that moment when I hit Record, but later, back in my apartment, I saw Wilbur’s fat book sitting on the desk with all those blank pages he’d left for me. Okay, I thought, let’s fill them up. It’ll give me something to do while stuck in this bullshit pandemic for the next few weeks.

But hush: Merenguero’s Daughter was talking.

“Back in the day, it would feature the hottest, up-and-coming merengue bands. And by the way, some of the songs from back then had some pretty insane titles and lyrics. That’s my trigger warning ’cause this is some racist shit here.”

She paused and looked around the rooftop a little nervously, as if unsure of what she was about to say, but also to gauge who was listening.

“There was a song that actually asked this question: ‘Qué será lo que quiere el negro?’ What is it that the Black man wants? That song was a huge popular sensation in the 1980s, and it was often played on El Show del Mediodía, which I would watch as a little kid. I wasn’t allowed to go to the studio because my dad didn’t want me there, and he was working, so he couldn’t watch me. Remember, he was a single father. He had to have control over me, and he didn’t want me going to anything like that.

“Dad was friendly with some of the dancers on the show and met a woman there. I don’t know what happened between them. They just said they were ‘muy amigos y muy queridos.’ I don’t know, I didn’t ask. But they remained friends over the years. She was always kind to me. Not like a long-lost mother figure, nothing like that, but she did teach me what to do when my blood came the summer I was eleven. I can’t even imagine what my father would have done. She disappeared from our lives when I was still a kid, but I always had good memories of her.

“I happened to run into her not too long ago, a few weeks before this shutdown. It was the craziest thing. I was at my favorite salon, getting my hair pulled, you know, how they do. The joke that everyone tells us, that even in heaven, Dominican hair stylists are still doing the curl around the brush pull with one hand, while they’re using the other to put who knows how many degrees of direct heat onto your hair to make it as straight as possible.

“Yeah. I used to do that to my hair every week, but then I realized that shit was whack for my hair and my head so I stopped.

“Anyway, I see her at the salon and ask how she’s been. At first, she doesn’t look happy to see me, to see anyone she knows. But then she begins this crazy story, which sounds incredible, but it’s true. The woman’s story began on September 11. Everybody was like, ‘Oh man, do we have to go back to September 11?’ It’s a lot, right? But maybe there is something in it that can teach us about the moment we find ourselves in, sitting up here on the rooftop. I call this story ‘The Double Tragedy.’

“Let me just say that when a story catches everybody’s attention in the salon, all the blow dryers stop. People can still get their hair put in curlers. They can still get color painted in. They can still get their hair cut. But if somebody has the floor and is telling a story that captures everybody’s attention, ain’t no blow drying going on. You can be sure of that.

“By the way, I have to mention, Eva was seventy years old and looked like she was fifty. She had gotten her natural gray hair blown out, but there was enough black showing through that you could tell that at one point her hair used to be phenomenally black. Now she was a distinguished kind of gray. She was also, let’s just say, a little enhanced in a few areas. And she carried it well. She made those tetas and that pa’trás look good on a seventy-year-old. Maybe that’s the way JLo is gonna look. We can only imagine. The point is, she looked hot and she was seventy years old.

“When she was in her fifties, after she had stopped hanging out at El Show del Mediodía and we had lost touch, she explained how she fell in love with a younger man. She did that crazy thing–she left her husband, with whom she had never been able to have a child. And she fell in love with this Dominican dude who, strangely enough, played in merengue bands. He was the percussionist, so he played a little of everything–claves, bongos, maraca, triángulo, cascabel, and yes, a percussive instrument from Peru made of dried goat nails. But he played jazzy, woke merengue, like old-school Juan Luis Guerra (before he became born again), Victor Victor, Maridalia Hernandez, and Chichi Peralta.

“Eva said she was hit with that crazy, crazy impulse to finally start listening to her heart and not give a flying fuck. She didn’t care anymore about the thing that keeps many people in Latin America and on la isla from doing the things they want to do, which is essentially, ‘El qué dirán. ‘What will the neighbors say?’ Eva was like,‘Fuck it. I don’t care. I’m in love with this dude. He plays in a band. And I’m leaving my husband.’

“Probably because they fell so deeply and madly and wildly in love, she got pregnant. It sounds unbelievable. You know, but like Eva said to the entire salon without a shred of self-consciousness, the sex was amazing. They were having sex all the time. With her husband, they just weren’t fucking, that’s all I can say. They just weren’t, they had stopped. But this guy was, I guess, around thirty and in his prime. Oh my God. How she talked about the sex! Well, it was so good that she ended up getting pregnant. That’s all I can say.”

“The hotter the sex, the faster the pregnancy,” interrupted Florida, 3C. Well, the bible had warned me she was a gossip.

“That’s scientifically bogus,” said Vinegar sharply, with a dismissive gesture. “An old wives’ tale, disproven years ago.”

“And where did you go to medical school?”

After a polite pause, Merenguero’s Daughter ignored them and went on.

“Sometimes it’s all about sex. Sometimes it’s about sex and passion. And the combination of those two things led to the miracle here. She was fifty years old, pregnant with the child of her thirty-year-old lover, now husband. Of course, she was considered scandalous. But by that time, she had already broken with ‘el qué dirán.’ Like, completely.

“And so had he. Her new husband had come from a very humble background in Santo Domingo, a neighborhood known as Villa Mella. The fact that he had made it as a musician and could provide for himself doing that was huge. He was happy. And had fallen in love with this incredible woman.They were totally nontraditional, but they made it work.They decided early on to never ever bring the war and words from outside into their marriage.

“All of us in the salon were just glued to Eva’s story. Yo! People ordered the salon helper to go get a round of café con leche because this story was just beginning and already it was so good.

“Then Eva gets back to September 11. On that day Eva happened to be down on Wall Street for an appointment, and she saw it. She saw the plane fly right above her head and crash into the first tower. She was going to an appointment in that tower. And she happened to be one of those unlucky thousand or so people, one of the unluckiest people–or maybe one of the luckiest, depending on how you see it–who happened to be right there when it happened. She stumbled and tripped in shock, badly twisting her ankle, but the adrenaline kicked in and she started running with her busted-up ankle. All she could think about was getting home to her husband and her two-year-old son.

“That’s all she wanted to do. Get the hell out of there, jump on a subway train, and go back to Washington Heights to be with her family. Yes, here she was, the age of most grandmothers. But she was a middle-aged woman who was desperate to see her toddler son and hold him in her arms again. Smell him. Eva was able to get on the subway, but she made it by a hair. It would have been a matter of less than an hour before the entire subway system was shut down in New York City. She made it home, walked in the door, and there he was, her gorgeous husband with the clear hazel eyes and the tight curls that looked like waves in an angry ocean. His hair was dark brown, but the tips were lighter and played with the cinnamon color of his skin.

“His name was Aleximas (a name created from Alexis and Tomas, very Dominican but don’t judge, yo), and he started crying when he saw her. The tears were rolling down his cheeks, like a baby’s. Because this unconventional couple loved each other so much, it didn’t matter that he was a grown man shedding tears. That was the kind of security that Aleximas felt with his wife, twenty years his senior. She made him feel safe. Life had been really rough for him, growing up in Villa Mella. Yeah, that was the truth. His home growing up in the DR had a dirt floor. I mean, I think that’s enough said, right?

“By now everyone was sipping their cafecito. Eva continued and talked about how deeply shattered she was by what she had witnessed on September 11. So much so that she couldn’t sleep.

“The doctor told her she had sprained her ankle and torn a muscle, so she had to stay at home with her leg up for several weeks. She was going stir-crazy. She was completely dependent on her husband for everything. He was going out to buy groceries. He was doing everything for her and for the family. He didn’t mind shopping, or even buying her tampons. She said it was just part of their unconventional love. He was a strong, centered Dominican man who was lucky enough to find a woman who said, ‘I don’t give a fuck what anybody says about me and what I do.’ Soy una de muchas mujeres as!

“Eva didn’t know how to handle these new emotions. You have to remember, back in 2001, people had never really heard about PTSD. The Iraq War hadn’t started. PTSD, what was this thing? She didn’t realize it, but she had it. She said she couldn’t get out of the depression. She’d be at home watching television, thinking about how she couldn’t move her leg because she had twisted it running away in horror from the most terrible thing she had ever seen. Every time she saw images from that day on TV–it was the only story on the news anymore, and they replayed it over and over–it was like she was back there standing on the street again, and she’d start shaking and crying.

“Aleximas was actually getting worried because her nightmares were keeping the whole family up. The little baby was picking up on his mother’s anxiety, and the baby wasn’t sleeping either now. Just like the plane had crashed into that tower, it crashed into their home, up-ending their lives.

“They couldn’t get out of the cycle of trauma. Together, finally, they made the difficult decision–which they knew, in the long run, was the best decision–to leave New York and go back to the Dominican Republic, back to Santo Domingo. Even though they had essentially made it in America, enough to be able to live their dream life in New York City, in a three-bedroom railroad apartment with big windows, a living room, and a separate dining room.”

“Impossible,” muttered Florida. There were murmurs of surprise from our little circle of listeners–I couldn’t tell if it was shock at the apartment or at Florida’s interruption. But she was just warming up. “How did they afford an apartment like that? These days that’s more than three, four thousand a month! Even back then–no! And if it was rent-stabilized, they’d be crazy to leave that behind.”

“Seriously,” said Eurovision. “That’s amazing. These days I can barely afford this dump.”

“Let her tell the story,” said Vinegar sharply.

“Yes.” Merenguero’s daughter was nodding. “A separate dining room on 172nd Street overlooking Fort Washington Avenue. Yeah. They were going to leave all that behind because the terror had come to their home and she couldn’t stop having nightmares.

“The plan they decided on together was that her husband and son would travel back to Santo Domingo first while she stayed behind to tie up loose ends at her work. Also, she needed the space to grieve and heal on her own, to work through her emotions without scaring her baby. She would be on her way within a month or two, at the max. And that was it. They were going to relocate to Santo Domingo and start their lives over again. They knew enough people there, things would work out.

“She looked at the flight schedules, and the soonest they could book a flight for Aleximas and their son turned out to be November 11. She was like, ‘Oh, there’s no way that I am letting my family travel on any eleventh of any month ever again. The eleventh está quema’o. It’s cursed.’ No flight was to be booked on that date ever again. Never. So she bought the tickets for November 12, and she took her husband and their baby boy to the airport and said goodbye at JFK.

“She was a nervous wreck, but she knew that she would be able to work out her terror now that they were gone. Maybe she would scream into a pillow three or four times a day–something she couldn’t do with her two-year-old around. And can you imagine if her husband saw her do that? He would really think she’d lost it, but she had lost it. She was traumatized.The only thing that was stopping her from going crazy was the love and responsibility she felt for her husband and son.

“So Eva said she dropped them off at JFK and drove back to Washington Heights. She put in a CD of her husband’s music, because that’s what people used to do back then, and it instantly put her in a better mood. The sadness at their airport goodbye gave way to relief that she would soon have a new life away from the tragedy. She smiled and laughed and danced in her driver’s seat and even got a little bit excited and wet just thinking about her husband and how she already missed him. Imagine. A grown woman feeling hot like a teenager. Ay!

“She was so blissfully unaware, lost in the first moment of happiness she’d felt in months, that she didn’t hear the news. When she got back to Washington Heights, she limped into her apartment and saw that the light was blinking on the answering machine (remember, this was 2001). She hit Play and heard the voice of her husband’s sister say, ‘Where is he? Where is he? How could this have happened? Why did you put them on that flight?’ Eva ran to turn on the TV, and that’s when she learned that Flight 587 had crashed in Far Rockaway, Queens, ninety seconds after takeoff.

“Flight 587 was so well known in the Dominican Republic that there was even a merengue named after it. And yes, her husband had performed it. They used to play the merengue ‘El Vuelo Cinco Ochenta y Siete’ on the plane, that’s how popular it was. The flight always took off early in the morning so that by the time you arrived in Santo Domingo, you could have your first almost-freezing cold beer waiting for you, sitting in ice. When beer is served that way it’s called ‘dressed like a bride’ because the bottle is covered in ice. It looks like it’s wearing a white dress.

“Her husband should have been drinking his beer vestida de novia, but instead, he and their little boy were dead. They had died instantly on Flight 587, on November 12, 2001. They had simply wanted to avoid flying on November 11. Everybody in the salon was completely silent by now, except for one woman who was sobbing.”

Merenguero’s Daughter looked around the rooftop at all of us. We had been shocked into silence, too. Even Vinegar. I reached for my phone, thinking she was done with the story. I wished I could call my dad more than anything right then.

“Eva just said, ‘Yeah, that was my life. I lived through a double tragedy.’” Merenguero’s Daughter was shaking her head as she talked. “I wiped my nose on my shirt and asked,‘How did you deal with it?’

“‘I didn’t,’ Eva said. ‘Well, you’re the first people that I’ve told about it. It happened twenty years ago, and I don’t talk about it. I buried whatever I could have my husband and my son. I locked up my apartment here in New York. And I moved to the Dominican Republic. No one knows who I am there or what I’ve lived through. I won’t tell you anything more about me because I don’t want you to ever find me.’ When Eva said this, she looked in my direction, and I nodded back to let her know that I wasn’t gonna reveal her.

“She looked at the women gathered around us in the beauty salon as if in defiance: ‘I don’t care what you think. A mí no me importa el qué dirán. I don’t care what anybody thinks about my life or my choices or what I do to deal with my double tragedies. Y así fue, y así es la vida,’ Eva added and then turned to her hair stylist. ‘Termina mi peinado, por favor.’ Finish my blowout.

“When the stylist was finished, this seventy-year-old woman left her stylist a twenty-five-dollar tip and walked out.

“I don’t know. What’s the lesson?”

On the roof, no one spoke. Merenguero’s Daughter paused, as if waiting for an answer, then shrugged again.

“Denial. Basically, denial worked for her. She compartmentalized to a point where she just told herself, I’m not even going to think about it anymore. Later on I found out Eva does indeed have a whole new life in the Dominican Republic. She did not remarry, but she has multiple suitors who call on her and treat her like a queen. Which basically means she’s getting some as often as she wants.

“So what do we do? You know, for some of us, we’re living through multiple tragedies: people losing family members, their jobs, their homes, their careers, and in some cases, their entire family. A lot of people are in denial. But they’re the ones who keep making us sick, and I’m sick of them. Here’s what I think–a little bit of denial goes a long way, but a lot of denial goes too far. Y colorín colorado, este cuento se ha acabado.”

Merenguero’s Daughter turned to Eurovision. “Dude,” she said, “put on some merengue now. I gotta dance this double tragedy away. Put on ‘Ojalà Que Llueva Café.’ I want it to rain coffee.”

“Who, me?” Eurovision asked, taken by surprise.

“You’re the one with the speakers.”

“Of course, of course.” Eurovision quickly straightened himself up and rose, fiddling with his phone. “How, um, do you spell that song title? Spanish is not one of my languages.”

She spelled it out. He tapped away and then stood up. “Ladies and gentlemen, may I present Juan Luis Guerra live, singing ‘Ojalà Que Llueva Café!’”

I’d never heard it before. The music was soft and longing, not the pulsating beat I’d expected.When it was over, a hush had fallen.

“That didn’t sound like merengue to me,” said Vinegar.

“That’s because it really isn’t,” said Florida. “That’s bachata.”

“Bachata is a kind of merengue,” said Merenguero’s Daughter, flaring up.

“Just saying.”

“Can you translate for us?” asked Eurovision.

“Ay hombre,” said Merenguero’s Daughter, “it’s a Dominican harvest song. A prayer. It’s about hoping the harvest will be good and that the farmers won’t suffer. But it’s more than that. It’s about a simple life and dreams and love of the land–really, it’s about who we are.” She closed her eyes and hummed the tune and then picked it up, translating into English, swaying slightly.

“I want it to rain coffee in the fields / Let there be a downpour of cassava and tea…”

When she was finished, Merenguero’s Daughter opened her eyes.

After a moment, Hello Kitty said, “That’s crazy, dying on the twelfth because they didn’t want to fly on the eleventh. It’s like they were cursed.”

“Cursed?” said the Lady with the Rings. “They didn’t do anything wrong. Tragedy like that is random and indiscriminate.”

“Being cursed is all in the mind,” said the Therapist. “Claiming you’re cursed or unlucky or victimized is how some people deal with tragedy, like this pandemic. I see it in my therapy. People even curse themselves–out of shame or guilt.”

“And your job is to uncurse them?” said Eurovision.

“You might put it that way.”

“I need some of that uncursing,” he said.

“My poh poh–my grandmother, on my mother’s side–she was an expert in curses,” said the Therapist.“She knew all about them. She had a unique system for handling them.”

“Like how?”

“Well, my mom is ABC and so am I, but Ah Poh was born in this tiny little village in Guangdong. I’ve never been there, but she showed me a picture once–a little gray stone house in the middle of nowhere, just rice paddies all around. My gung gung used to catch fish in the river for dinner. They came over just before the war to San Francisco and settled in the Sunset District, and they never went back. I don’t even know if that little house is still standing, or if it got destroyed in the Revolution, or what–a lot of stuff was.

“Anyway, just after I was born, my gung gung died and my poh poh moved in with our family, and she took care of me and my sisters while our parents were at work. She used to let us play with the jade bracelet on her wrist; she’d worn it since she was a little girl, and it was still tiny, but her wrist had grown and it wouldn’t come off anymore. My mom had one just like it; it used to get all soapy when she washed the dishes and covered in potting soil when she worked in the garden. Ah Poh gave one to each of us girls when we were little, tried to get us to wear them, too, but I couldn’t stand the feeling of it around my wrist. Like handcuffs. I think Mina and Courtney still have theirs; I don’t know what happened to mine.

“Ah Poh was tiny, like five feet tall at most, and every year she got a little shorter. She wore these quilted floral vests, and she had that hunch old Chinese ladies get–you’ve seen them, if you’ve ever set foot in Chinatown. Quasimodo, my sisters and I used to call her, until Mom heard us one day and smacked the shit out of us. It’s osteoporosis, that’s what I learned later, due to childhood lack of calcium. Tiny fractures in the spine that break and reheal over and over, like a cup that’s been mended with too much glue. At least, that’s what they told us in premed.

“But don’t get me wrong–Ah Poh looked like a sweet little old lady, but she was fierce. One time on Grant, this guy tried to grab her bag. She wouldn’t let go. She yanked it back so hard he lost his balance. Then she gave him a royal cussing-out so loud he just lay there, like he’d been fire-hosed. When she finished, all the shopkeepers were frozen in their doorways, spectating, and the guy scrambled up and took off. I remember I was just standing there, holding the pink plastic bag with the fish and the bunch of bok choy we’d bought for dinner, and Ah Poh turned to me and said, ‘Okay, come on, neui neui, let’s go home.’ Like nothing had even happened.

“Well, after my sisters and I went off to college, we were grown up, we were busy, we were dating and working, and we didn’t call home as often. Ah Poh started doing the typical grandmother thing: nagging at us about being single, how we’d better hurry up and find somebody. ‘Aren’t you lonely,’ she’d say over the phone, ‘without a family, how do you have a purpose in life.’ I suggested this was projection on her part–with all of us gone, she had a lot of time on her hands.

“‘Nuh-uh,’ she said, ‘don’t you try that psycho-ology on me, neui neui. That doesn’t apply to Chinese people. That’s only for gweilo.’

“I had switched from premed to psychology by then, and she was the only one who wasn’t giving me a hard time about it. My parents, of course, didn’t consider psychology medicine–they wanted me to be a real MD doctor. In fact, I think they’re still holding out hope. It’s a stereotype, but it exists for a reason, you know? What it is, is that they went through so much to get here. They think about Ah Poh growing up in the middle of that rice field, and all those years of scrimping to pay tuition, and we’re just going to throw all that away and follow our dreams and become poets or postmodern interpretive dancers or whatever? We’re their investment on their down payment of suffering, and they are for damn sure going to get their returns.

“Anyway–Ah Poh kept giving me a hard time about not having anyone.

“‘What happened to that Alex?’ she said.‘I thought that was going so well.’

“Alex had recently left me for my friend–now my ex-friend–and on top of that he still owed me nine hundred dollars that I’d lent him, which I was pretty sure I wasn’t going to get back. When I told Ah Poh that, she made a clicking noise with her teeth.

“‘Okay,’ she said, ‘I tell you what, neui neui. I’m going to curse him.’

“Ah Poh had plenty of superstitions, we’re a superstitious people–though maybe everyone is. Don’t turn the fish over on the platter or your boat will overturn. Don’t put your purse on the ground or you’ll become poor. Don’t give scissors and knives as presents or you’ll cut the friendship in two. Don’t say the number four. As kids, we couldn’t turn around without stubbing our toes on another thing that would bring us bad luck. But cursing is not any ancient Chinese practice I’d ever heard of.

“‘What do you mean, curse,’ I said.

Apparently, she’d learned it from her friend Marcie, who she met playing bingo at the neighborhood church on Tuesday mornings.

“‘I thought you thought bingo was boring,’ I said.

“‘I do,’ she said, ‘but it turns out, so does Marcie. So I taught her mah-jongg, and now we play that every week instead. And we go to the casino on Thursdays. Senior discount day.’

“‘Wait, what do you play at the casino?’ I asked.

“‘Slots,’ she said–a little surprised, like it was so obvious. ‘Sometimes some blackjack, too.’

“Marcie had a ritual: whenever someone wronged her, she’d write their full names on a slip of paper, roll it up, and freeze it into an ice cube. And then leave it there in the freezer. Forever.

“‘It works,’ my poh poh insisted. ‘This contractor overcharged Marcie for repairing the roof, so she wrote his name and froze it. Two weeks later, he got sued by the city for letting his license lapse. You tell me that Alex’s full name. I’ve got a piece of paper right here.’

“I didn’t feel I had anything to lose, and anyway arguing with Ah Poh was usually a losing battle, so I recited Alex’s full name–first middle last, right down to the III–and she wrote it on a piece of paper and told me she’d pop it into the ice cube tray as soon as we hung up.

“And wouldn’t you know it, a month later I heard through the grapevine that my ex-friend cheated on Alex with his sister–and now they were a serious thing, and a week or so after that I saw pictures of her three-carat engagement ring on Facebook.

“After that, my sisters and I started calling Ah Poh whenever we had grievances we couldn’t right through regular, non-curse means. When Mina got understudy in her show, Ah Poh froze the actress who got the lead, and just a few days later she broke her foot and Mina stepped in. When Courtney’s boss at the firm made a pass at her, Ah Poh wrote down his name, and later that year he got caught falsifying evidence and was disbarred. And when the neighbor across the street from my parents hung up his ‘Trump’ sign, with ‘Send Them Back’ hand-scrawled across the top, she wrote his name down, too. My mom said last she heard, he got shingles and had to stay inside for months. We’d call Ah Poh with an update each time we heard another justified misfortune. ‘Guess what,’ we’d say, and inject the next little hit of schadenfreude.

“She took it seriously. She kept those ice-cube curses in there, in a gallon Ziploc bag at the back of the freezer behind the ice cream and turkey leftovers. One time, when I was still living in the Bay Area, she called me.

“‘Power’s out,’ she said.

“‘Ah Poh, are you okay?’ I asked. ‘You need help?’

“She made that clucking noise again. ‘I’m fine,’ she said, ‘I’m not afraid of the dark. But listen, neui neui, your mom’s not home, and I need you to do something.’

“What she wanted was for me to come by with a cooler full of ice.

“‘Ah Poh, I just got home,’ I said. I was living in Oakland then, and I didn’t want to cross the bridge for the third, and then fourth, time that day.

“‘Aiyah,’ she said. ‘All these things I do for you all these years, and you won’t do this one little thing for me?’

“When I arrived forty-five minutes later, lugging the big red-and-white Coleman cooler I used on camping trips, she met me on the steps with the bag full of curses in hand.

“‘Good girl,’ she said. She swiveled the cooler open and nestled the bag down into the ice and shut it again, her jade bracelet clink-clinking against the lid.‘There,’she said.‘That should hold it until the power comes back on.’

“It did, and in the morning, when I called to check on her, the first thing she told me was that the cubes were back in the freezer. Not a single one had melted.

“She died last fall, at the ripe old age of ninety-six, shorter and fiercer than ever, still going to the casino with Marcie in her big old visor hat right up to the end. I’m glad, in a lot of ways, that she went before all this started. Believe me, she’d have a lot to say about Covid and all of it. Pity the poor soul who might have said any of that ‘China virus’ bullshit in her hearing.

“Anyway. I went home in February, right before everything shut down, to help my mom sort through Ah Poh’s things. The last night I was there, when everyone was asleep, I went to the freezer. The curses were all still in there, little frosty cubes with the slips of paper cloudy white inside. I wanted to know the full scope of our anger. To see them all laid out in front of me, all the people who’d done us wrong over the years. Who had my poh poh written down for herself? Who were the ones who’d done her wrong?

“I spread the ice cubes out on the table and watched them melt, slowly. The kitchen was cold, and it took a long time. But finally, there they were: little rolls of paper, finally freed, soggy in the growing puddle. I started to unwrap them.

“And would you believe it? They were blank. Every one of them. Just blank slips of paper rolled up and frozen in ice. I still don’t know what to make of it. ‘Psycho-ology,’ Ah Poh would have said.”

The Therapist lapsed into silence, and if it weren’t for another siren cutting the air, you could’ve heard a pin drop on the rooftop of the Fernsby Arms.

“Whoa,” murmured Hello Kitty.

“Maybe it was a kind of therapy,” said Vinegar. “She wasn’t out to curse others, but to gratify herself.”

“Or,” said the Lady with the Rings, “it was because her curses were too terrible to be written down in words. She spoke them into the paper.”

The Therapist didn’t offer an explanation herself. The group fell silent. It had gotten late. Night had dropped. The midtown skyscrapers, with their lights strangely off, were like great dark vertical whales in a sea. Church bells began to toll in the distance, echoing through the empty streets. Eight o’clock. No one seemed to be sure what to do next, and eventually, subdued by the stories, people began gathering up their things to go down to their apartments. I casually picked up my phone and hit the stop button as I slipped it into my pocket. The stories had reminded me of my dad, locked down and all alone in the nursing home, cut off from the world and human contact, and I felt a wave of nausea.

Back in my room, I sat for a long time at the super’s peeling desk, with his massive tome in front of me, thinking about everything. I wasn’t the slightest bit tired. The stories I’d heard that night were still ringing in my brain. I picked up the chewed Bic and opened the book, or rather bible, to the “Observations and Notes” blank pages. Then I took out my phone and began to replay the stories that had been told, along with all the chatter and talk in between, stopping and starting and laboriously writing everything down in longhand, adding my own commentary and connective material.

It took me a couple hours. When I was done, I leaned back in the creaky chair and stared up at the stained, popcorn-foam ceiling of my apartment. I had a feeling I was one of those people the Therapist talked about, who curse themselves. My life seemed to be a long string of self-cursing. But putting the evening down on paper felt like a purging of sorts. You always feel so much better after a really good vomitus.

That’s when I heard soft footsteps in the empty apartment above me: 2A. I knew it was empty because the super’s bible told the story of what happened to the previous tenant. He had gone crazy in there, and when they finally broke the door down to take him to the hospital, they found thousands of dollars in twenties crammed and folded into every nook and cranny. When the cops asked the crazy guy what it was about, he said it was to keep out the roaches and evil spirits.

Tomorrow, I’d better check the apartment for squatters.

Ordering Options

Ordering Options

Audio Excerpt

Audio Excerpt

Set in New York City in 2020 during the opening days of the global pandemic, the project was the brainchild of Authors Guild president and novelist Doug Preston as a fundraiser for the Authors Guild Foundation. Preston conceived the book as a collaborative story, an innovative sort of novel, written with contributions from a wildly eclectic group of authors drawn from the full range of narrative genres. Each author has chosen or developed a character who lives in the building and serves as the voice for their story.

International Links

International Links

Excerpt

Excerpt

Ordering Options

Ordering Options

Audio Excerpt

Audio Excerpt

International Links

International Links

Excerpt

Excerpt